Digital Health Rewired - Reflections on future healthcare

6 minute read

Applying design to healthcare and life sciences challenges is an important strand of Nexer's work, both here and in Sweden. To learn more about those challenges, and how people within healthcare systems tackle them, I went along to the Digital Health Rewired conference, in London’s Olympia.

Francis: My impression of the day was that there really is a lot of energy and determination, particularly from people in or connected to the NHS, to make the most of data and technology to improve health and social care for all of us. And it isn’t just grand speeches: speakers shared what they’re doing, and how they’re doing it, to encourage others to do the same. It was clear that human-centred design is an important facet of this, in terms of driving healthcare innovation that truly brings value to people.

Systems thinking and access to care

Something that struck me about the conference was the scale. I don’t mean the size, or the number of people (oh, the noise level in an exhibition hall!) - I mean that talks and discussions covered topics from the system level, down to the more granular level of specific tools and interactions. I think it’s often interesting to know at what scale we’re working, and to be able to move between layers or levels.

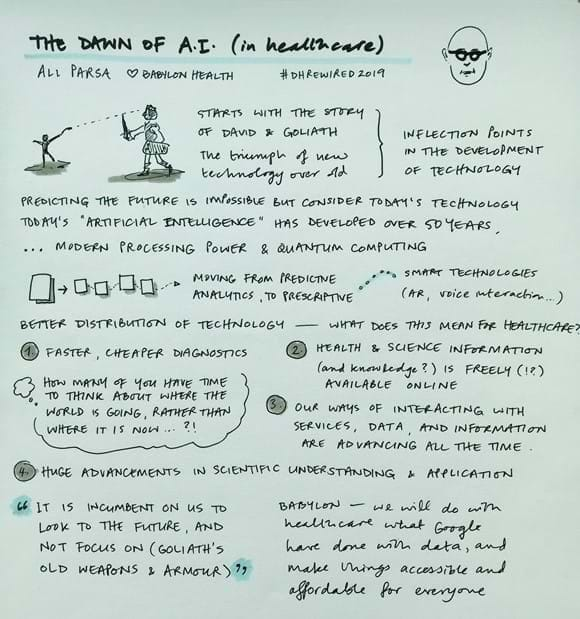

In the first talk that I attended, Ali Parsa of Babylon Health viewed healthcare innovation through the lens of futurism, and talked about “inflection points” in the development of technology. There is an implicit design challenge in the goal of better, more suitable distribution of technology.

How many of you have time to think about where the world is going, not just where it is now?

His talk made me think, though, of impacts and consequences – something that we increasingly actively work on with our clients. Due to the pace layering and interconnectedness to systems, we might need to consider impacts and consequences quite broadly when we strive for innovation and perhaps disruption of conventions.

For some time now, my colleagues and I have been analysing the challenges of access to healthcare, where scale and focus are important considerations, too. We’ve begun to gather and share information about inclusive healthcare.

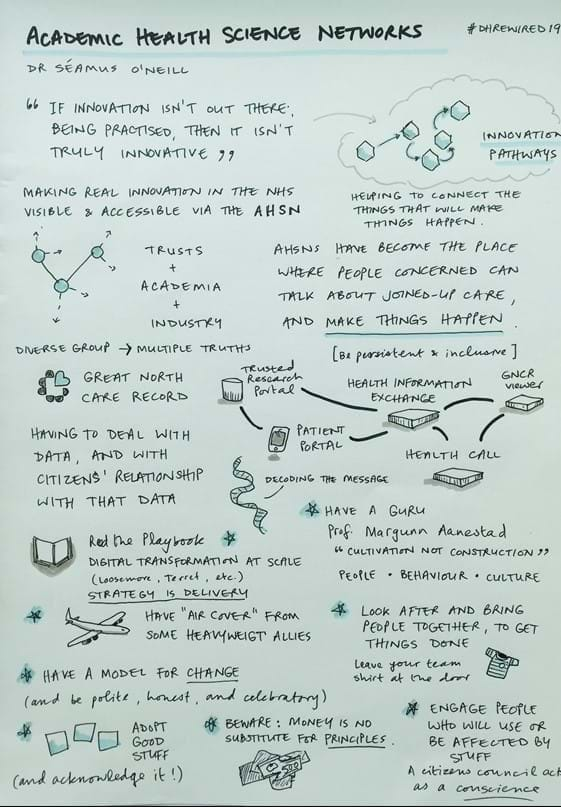

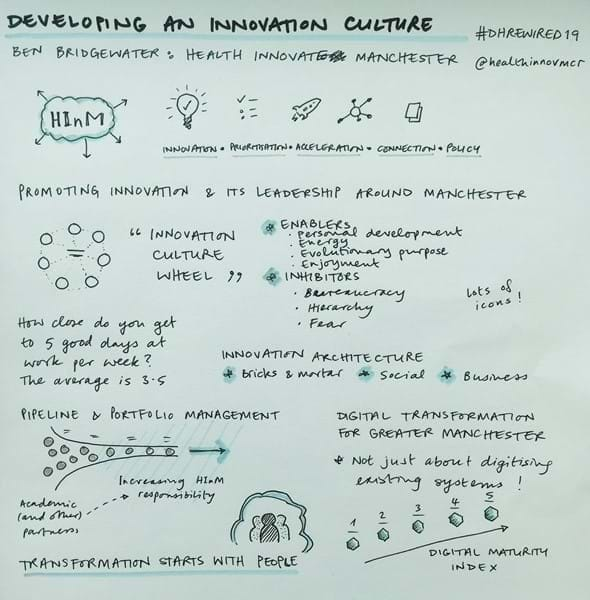

Two of the day’s talks that stood out to me the most were from Séamus O’Neill, Chair of the AHSN (Academic Health Science Networks), and Ben Bridgewater, CEO at Health Innovation Manchester, who talked about nurturing an innovation culture across the NHS.

Both shared advice and stories about bringing people and groups together, and making things happen. Séamus shared a great set of tips from his experience with the development of the Great North Care Record, and explained how AHSNs identify “innovation pathways”. He was keen to stress that having a diverse group (including designers) brings “multiple truths” and a breadth of experience.

Ben focused on Health Innovation Manchester’s promotion of innovation and leadership around Manchester, and how they partner with academic and industry experts, to move from ideas to implementation. It was great to hear his perspective on digital transformation, and what it takes to make things work. As with the AHSN approach, people are key to this, and Ben referred to concepts from business innovation as a helpful structure, such as identifying enablers and inhibitors of change and innovation.

Engage people who will use, or be affected by, what you make

Involving people: "Designing With"

Another theme that stood out to me was the importance of the people involved in all of this; of involving people, and designing "with" as much as “for”. Given my line of work, that was of course music to my ears. Having considered the wider, system-level view of how health and care services can be improved, I noticed that a number of speakers emphasised the importance of diverse teams, of patient voices, and of maintaining engagement throughout processes.

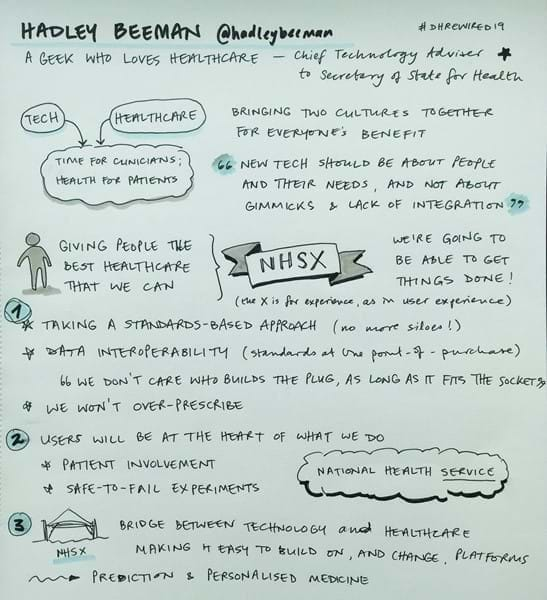

This message was threaded through a number of the talks: Hadley Beeman gave a great talk about NHSX, explaining that, “… the X is for experience; as in, user experience”, and emphasising the point that users will be at the heart of NHSX’s work. During the day, and in between talks, I chatted with some of the vendors of tools and platforms who were there, manning stalls. I asked each of them about how they involve “users” in the development of their products and responses were mixed.

The companies typically had big development and sales teams, and the user interfaces of many products looked pretty nice, but few of the representatives could tell me how they knew that their product was good, nor how they continuously gather and act on user research. My guess is that they simply don’t. Over a pint, at the end of the day, I chatted with an anaesthetist, who opined that she and her colleagues have to use software that everyone knows is awful but is the only choice; sometimes due to inertia, and sometimes because a hospital or trust has bought something else, and this is part of a suite. At best, bad software wastes time.

While this is obviously frustrating, there were speakers and groups at the conference who are doing something about that, from the inside.

Hadley Beeman, for example, made it very clear that NHSX aims to bring tech and healthcare together, to do great things for patients (better healthcare) and staff (more time to actually care for and treat patients). Hurray!

"Wouldn't it be sensible to make all these apps usable and accessible by default?"

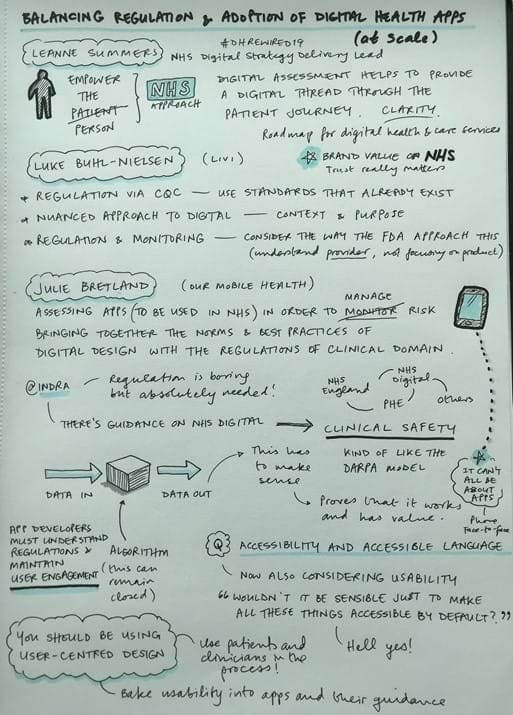

The final session I attended was a panel discussion on balancing regulation and adoption of health apps at scale.

Representatives from the NHS and from industry partners engaged with the audience in energetic discussions related to the promise and development of digital healthcare apps. In this session, the panel discussed how apps, in particular, can be developed and assessed, so that they are good enough to be included in the NHS App Store.

Leanne Summers spoke about how she and her NHS colleagues are transforming digital health. Her points were echoed by Indra Joshi, who added that while regulations might be boring, they must be understood by companies who are developing apps. In addition, these companies need to maintain user engagement - so, ideally, things like continuous user research, encouraging developers to go and see things in use, and good, old usability testing!

App developers should be using user-centred design principles, and patients and clinicians should be part of the development process.

During this session, discussion of accessibility was a hot topic, with one audience member encouraging more accessible language (hello, content design), and a woman from NHS England asking, “Wouldn’t it be sensible to make all these apps usable and accessible by default?”. Absolutely, it would!

Our work, and those of groups like Our Mobile Health and ORCHA aim to do just that. Recently, we’ve been working with NHS Digital, to help support their work on accessibility and inclusive design, and it's clear that this user-centred thinking and practice is increasingly firmly embedded in how the NHS is operating.

There’s no doubt that the NHS faces many challenges but I was glad to hear positive, motivating talks of what people are achieving despite those challenges. This work is happening at different scales, and it’s not just about throwing technology at a problem, and assuming that will fix it. Rather, it’s about connecting and supporting people, about taking a design mindset to development and user engagement, and encouraging innovative ways for people to access great healthcare.