Older adults: Are we really designing for our future selves?

Creating tech for older adults often comes with the advice to “design for our future selves”. But is it good advice? Elizabeth Buie explains how it helps — and how it gets in the way.

I have a talk/workshop that I give from time to time on accessibility for older adults. The idea arose in 2015, when I was listening to a talk on designing “for our future selves”. At one point I heard the speaker say something like, “studies have found that older adults aren’t familiar with scroll bars, so don’t use them”. No no no, I thought to myself, it’s not that simple! I mean, I had been familiar with scroll bars since the mid-1980s, and in 2015 I was already “older”. So I started thinking about how the slogan helps and how it doesn’t help, and my talk emerged from that. This post offers a high-level view of the points I make.

But first, why do we need to design for older adults? Besides the general principle of inclusion (and I’m sure you’re on board with that!), we have two reasons: growing demand, and unmet needs.

Growing demand. The UK Office for National Statistics (ONS) have data showing that “recent” Internet use by older adults in the UK grew substantially from 2013 to 2020 (Figure 1). Recent use increased by 34% in the 55-64 age group, 55% among 65-74s, and a whopping 114% among people over 75! Interestingly, that same period saw little or no increase in recent use by younger people, even declining slightly in the 16-24 age group.

Figure 1. Recent Internet use by age group in the UK, 2013 vs 2020

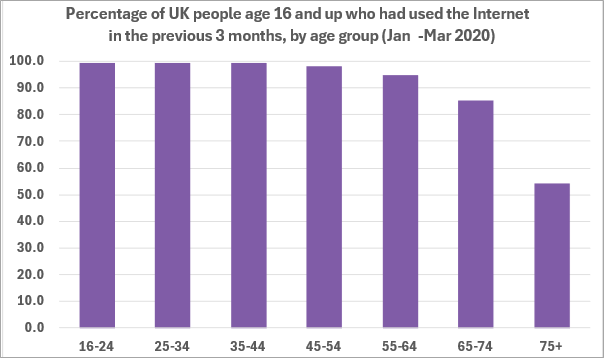

Unmet needs. Despite using the Internet more than they did, older adults still use it less than younger people do (Figure 2). In all age groups under 55, recent use in 2020 was 98% or higher. But after 55, use started declining with age — 94.7 in the 55-64 group and 85.5% in the 65-74 group — until it got down to only 54.1% among people 75 and older. That’s quite a decline!

Figure 2. Percentage of UK people age 16 and up who had used the Internet in the previous 3 months, by age group (Jan-Mar 2020)

As you see, we still have some work to do. So can we use design to help meet older people’s needs? I think we can. Some of the accessibility issues that older adults commonly face are often overlooked in design, and if we address those we will go a long way towards making technology easier for older adults to use.

Of course, design is the not only thing that impedes older adults going online. Economic and social factors play a role as well. But good design can make a difference, if we know how to accommodate changes that tend to occur with age.

This slogan — designing for our future selves — is good in one way: it helps us empathise with older users and engage with their stories. On the other hand, it also brings a problem that offsets those benefits. The slogan implies that all of the challenges that today’s older adults face in using technology are the same as the ones that will confront us in 20, 30, 40 years.

Speaking of empathising, let me offer a brief (but important) point: Do not call older people “elderly” to refer to their age alone. That word gives the impression that the person is frail or vulnerable, not just older. Call them older adults or older people.

The slogan has two key problems: We all age differently, and some of the “guidelines” offered for older people are based on something other than age alone.

We all age differently

Let’s say you’re 40 years old. Do you honestly think your future 70-year-old self will have exactly the same impairments as your 70ish parents do now? Do you think that you and your best mate from school will have identical impairments, as the two of you become older adults?

I didn’t think so.

Some design considerations will always be with us. Limitations tend to come on us as our bodies age. Eyesight dims, colour vision changes, hearing declines, joints lose flexibility, memory isn't what it once was. Here are some key things that affect our use of tech as they change:

- Senses: vision, hearing, touch (also smell and taste, but those are less important in technology use — for now, at least)

- Movement: co-ordination, comfort, speed, steadiness

- Cognition: memory, speed of learning, information processing, reaction time

- Attitude: Confidence with new tech, willingness to learn new technologies and procedures

All of us will experience some or even most of these changes as we grow older. Knowing this, we might be tempted to use ourselves to model the future. But each of us will age individually. We will experience the changes at our own pace and in our own unique ways. No person’s experience will predict or mirror anyone else’s. It just won’t.

Here are some ways in which age-related changes differ from person to person:

- Onset: Impairments begin at different ages in different people.

- Speed: They develop more quickly in some people than in others.

- Severity: They have different levels of impact on different people.

- Occurrence: Most impairments occur in some or even most people, but not in everyone. Presbyopia — the one that makes us need reading glasses — is the only impairment that everyone eventually gets if they live long enough.

For the foreseeable future, bodies will continue to develop age-related limitations. Older people will always face these challenges simply because they are older, and our designs will always need to accommodate them. But we cannot assume that our own ageing will reflect the general case.

If you’re designing for YOUR future self, you’re going to miss a lot.

Some of the so-called “guidelines” we see for older adults are based on something other than age

They centre on people’s knowledge and life experiences.

Although these guidelines (like the caution against using scrollbars) may be somewhat appropriate for products we design today, they will evolve — and probably rather rapidly. Knowledge changes; life experiences change; socio-economic conditions change; the world changes. People’s knowledge and attitudes about technology will change along with them.

Perhaps people will always become more hesitant to learn new technologies as they grow older. This change, I suspect, may be related to decreases in speed of learning and cognitive processing. And maybe older folks will always become more and more frustrated when technology doesn't work as they expect. But the specific design features that frustrate and thwart people will change as technology evolves.

We will always have to ask ourselves one key question.

As designers of products for older adults, we need to understand which challenges we will always need to accommodate and which ones will evolve. It all boils down to the difference between challenges that people have because they are older — and challenges they have because they are older NOW. So when you see a design guideline that refers to what people know or what their life experiences may be, take it with an entire shaker of salt.