The Post Office Horizon Scandal through a Service Design lens: Part two

6 minute read

In the second of a two-part series, Amy explores the Post Office Horizon Scandal from a service design perspective, focusing on the failures in the Processes, Technology, and Touchpoints service layers

Please note: If you haven’t read part one of this two-part series yet, I’d suggest you go back and read it.

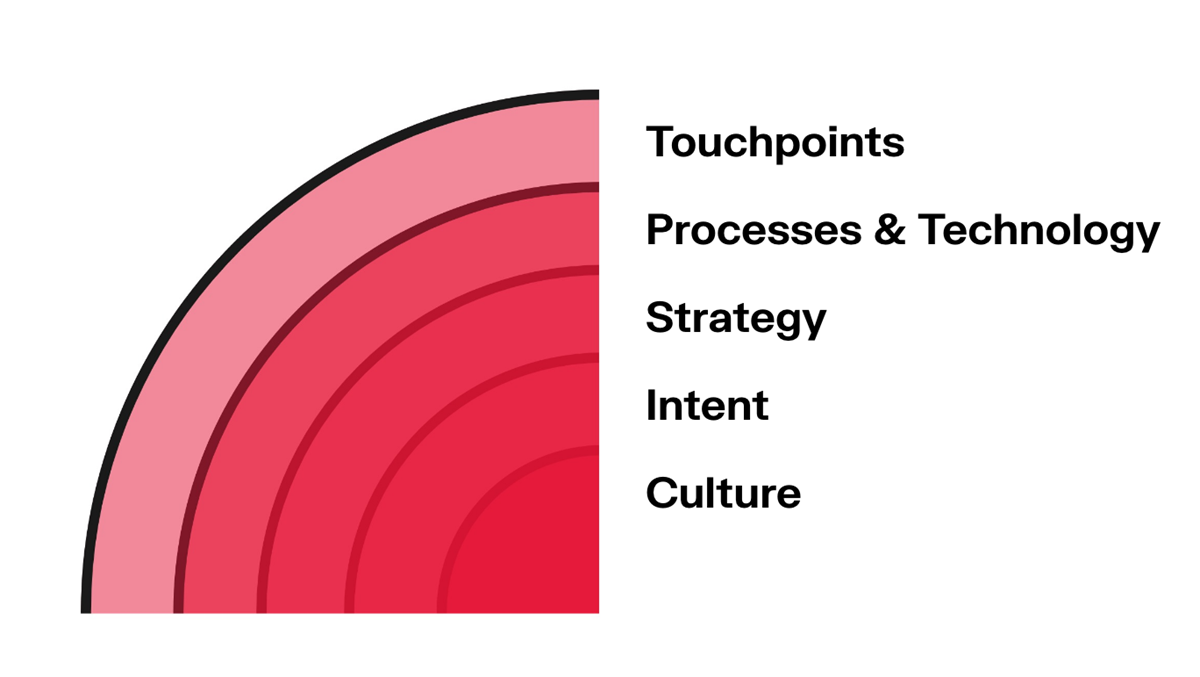

To refresh those of you who have read part one, I became interested in the British Post Office Horizon Scandal, and I started thinking about what had gone wrong from a service design perspective. I used the first blog post to examine what failures occurred on different “pace layers”. In part one, that was Culture, Intent, and Strategy. In this second part, I'll continue to look at Processes, Technology, and Touchpoints. I’ll outline the impact of the failures on these layers, and I’ll explore the potential role of service design methods in preventing such failures in the future.

Here's a reminder of the service pace layers that our service design team often uses as a lens through which to view what we’re working on:

Figure 1: Pace layers diagram

So, without any further ado, let’s get stuck in and look at Processes.

Processes that were not thought through

Processes are a set of actions taken to achieve a particular goal. Inside organisations, processes often involve a combination of people, systems, and data. Processes tend to be changeable and can be messy, evolving according to the ongoing needs of an organisation over time.

A development process “like the wild west”

Through Horizon’s development, there was no recognised design process. At ICL (later Fujitsu), no designated designers were employed – although not unusual for the time (mid-90’s), it’s a point worth remembering as we look at what happened during the development of Horizon.

Source: https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/uk-news/post-office-scandal-what-actually-31852535

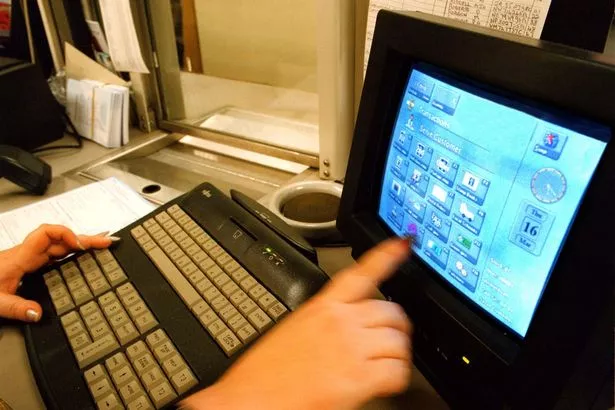

In 1998, ICL employed David McDonnell to conduct a review of the Electronic Point of Sale Service (EPOSS) counter team and their code. The EPOSS counter team were responsible for developing the software for the main touchpoint Sub-Postmasters or Branch workers. They would use the EPOSS counter to serve customers and do their weekly accounts.

In David McDonnell’s inquiry interview, he says on design, “It should start with the design documents, that’s what you’re building against. They weren’t in evidence. In fact, they weren’t even in the building when I arrived.” David goes on to explain that design documents such as architecture diagrams where reverse engineered to pass audits.

This was just one example of poor practice in the process of developing parts of Horizon. It was known internally by ICL that the software from the EPOSS team was performing badly and that they were running up hundreds of test faults a month. In fact, this is why ICL hired McDonnell. McDonnell’s report concluded that the code was poorly written, with no standards, no naming conventions and basic programming errors. There was no documentation, unit testing practices or peer reviews. The lack of rigour and oversight accumulated in poor code that we now know resulted in errors and bugs that went on to ruin people’s lives.

It was clear that the system at the time was never fit for purpose in a real- world environment

McDonnell’s report recommended that parts of the EPOSS code, especially that handling the account module, should be scrapped and rewritten. The account handling module was needed to ensure accurate accounting. The report and recommendations were minimised, and while some code was refactored, the account module was not scrapped or rewritten. This shows a serious flaw in risk assessment and decision-making processes on ICL and the Post Office’s part. There was likely a myriad of reasons for this: pressure to meet deadlines, concerns about losing money, or ICL’s worries about seeming incompetent to the Post Office. These are likely cultural and strategic pressures (which we discussed in part one). Had David’s report been taken seriously, and his recommendations actioned, we could be looking at a very different outcome today.

What could help in a situation like this?

Agile project management builds in resilience and adaptability

Whilst not strictly speaking part of Service Design, adopting agile methodologies can help increase resilience to changing plans, and can provide an opportunity for design to be continuously involved. This iterative approach more easily accommodates evolving requirements and can adapt to changing user needs and context.

Ignoring users concerns

Horizon was trialled from 1998, involving 300 users across different Post Office branches in England. However, ICL had conducted no prior discovery work to understand user needs.

During a meeting with a group of trial users in the Northeast of England in 1999, many flagged problems with the EPOSS touchpoint. In fact, “Seven sheets of comments from Northeast had been passed to the programme manager.” Many users had issues with balancing accounts and had to work late into the night to resolve issues. They said, “A tragedy was not far away if something was not altered soon.”

In this meeting, the then programme manager, Mr David Miller, gave them an ultimatum: “Do you want the system or not?” and asked them to raise their hand if they didn’t. Nobody did, so the Sub-Postmasters’ concerns went unacknowledged, and a few months later the Post Office signed off on the system.

The Post Office had clearly made some effort to seek user feedback. However, their culture affected their response to negative feedback. This process seemed more like a tick-box exercise than one genuinely interested in user needs and feedback.

What could help in a situation like this?

Research to understand users and their needs

Conducting discovery research before starting development of Horizon would have enabled it to be designed with user needs in mind. Today a government service such as this would likely be held to the GDS Service Standard. In our Service Design team, we follow the Service Standard while working on public sector programmes. We also apply these principles where possible when working on non-GDS projects too.

Co-design gives users a seat at the table

Designing Horizon alongside Sub-Postmasters using co-design methods would have ensured that the service was developed in a user centred way. Sub-Postmaster's experience, concerns, and feedback would have been heard earlier, avoiding systemic failure later down the line.

How flawed data processes led to convictions

Issues with Horizon’s data processes had a big impact on Sub-Postmasters and often led to their subsequent convictions.

Auditors and investigators at the Post Office lacked training in interpreting data logs and their limitations. The data provided by Fujitsu was filtered to make it easier to read but masked crucial information. Those at Fujitsu who provided the data to the Post Office were unaware that it was being used for prosecutions until 2006. Finally, according to the 2013 report by Detica, the Post Office had no real control over its internal accounting systems during its Horizon-related prosecution spree. This suggests that it could not assess whether the money was actually missing or not.

The failure to secure data integrity and create due diligence around using data, combined with a misguided a ‘computer is always right’ law, led to the wrongful prosecution of Sub-Postmasters.

I won’t be looking at the law in this blog post. However, there is an increasing amount of evidence to suggest that Post Office may have lobbied for the law that led to so many innocent people being convicted.

What we can learn here, is that services do not exist in a silo. Services exist as part of wider eco-systems, which can amplify faults and turn them into disasters.

The dangers of performance metrics and patching over bigger problems

An important part of any service is a helpline for when something goes wrong. Services will always have failure points. When they do, we need to make sure someone can help users recover from those failures. Horizon was no different, and there was a Fujitsu helpline that users could call for help and support.

Performance metrics like the speed of answering and call length were used to measure Fujitsu’s staff performance on those helplines. This can incentivise interactions that lack thorough investigation and due care.

Fujitsu’s helpline staff would feel pressure to resolve transaction problems within a 3-day limit, or Fujitsu would suffer a penalty fine from the Post Office. These penalties incentivised short-term workarounds over rewriting code. The helpline had its hands tied, and “It was widely accepted that the underlying or root cause was that the system was crap. It needed rewriting.”

Those same staff had the ability to make corrections to live transaction data on the branch computer without the sub-postmaster knowing. This was because the fundamental issues required rewriting the code, and it was quicker to correct the figures manually. This remote access later became the “smoking gun” that won the Sub-Postmasters' group action case against the Post Office in 2019.

Ultimately the poor processes in place for the helpline prioritised speed over stability, leading to bugs and errors festering, and not being fixed.

What could help in a situation like this?

Designing for change management

Something that we consider in our service design approach at Nexer is how we design for change. When a new service is designed, it’s about more than the shiny new piece of technology; many organisations make the mistake of not considering the other elements that make up a service. The people operating a service face a lot of change when it is redesigned. They need to be considered and included in the design process. In fact, the people that run a service have a significant impact on the experience users receive. If their job is needlessly difficult or they haven’t been trained properly, it’s the user that ultimately pays the price.

Measuring the right things

Being able to track the success of services and the value they create for the different actors involved is critical. How do we know that something is “working” or “better”? As noted earlier, this is not simply about performance metrics. Indicators of success should also consider the attitudes, experiences, and different perceptions of value of the people using and providing services.

The flawed technology at the root of the problem

The technological problems in Horizon were many, and they ripped through the other layers, causing many knock-on impacts.

We've already mentioned how poor the development process was, and unsurprisingly this resulted in poor development solutions.

Some of the technology problems:

- Horizon relied on the internet to reconcile records between Post Office hardware and a remote server. An anonymous source has said that “The asynchronous system did not communicate in real time but does so using a series of messages that are stored and forwarded” and that “messages from the centre may overwrite data held locally.” This was at a time when many places did not have internet, and those who did had dial up. The flaw was especially problematic in rural branches with unreliable internet. There was a failure to consider how this could affect the system's reliability.

- The hardware reboot rate after an error was much higher compared to a competitor, raising concerns about reliability.

- There was no agreed data dictionary or software to monitor what type of messages could be written to the data store. This meant that there was no standardisation for how transactions were recorded, and they would change as different developers worked on the system.

- The main user interface was based on a commercial product built by the Escher Group called riposte. There was an ongoing issue with this product called “riposte lock” where the interface would lock up and become unresponsive to users' inputs. The problem had “been around for years and affects a number of sites most weeks” and Fujitsu knew about it but had little control of when Escher would fix it.

There would be errors upon errors that would build up and snowball, this made it difficult for helpline investigators to work out what was happening and find the root cause of a problem. Some of the bugs would take years to fix due to this. The number of bugs and errors was likely due to poor code and a lack of error trapping. The poor error trapping led to silent failures in the system without alerting users to act.

Most seriously of all, both the Post Office and Fujitsu released Horizon despite knowing about a 0.60% error rate in the account-balancing software. They did not consider how this would affect the governance and policy layers. They also failed to consider the catastrophic impact this would have on sub-postmasters, who had to repay any discrepancies in the balance according to their contracts. Instead, they felt reassured that 0.60% would be minimal to the Post Office’s profits and failed to consider their users. This is a stark reminder that when we talk about “users”, we are talking about people who have homes and families and livelihoods.

It is safe to say, there were far more technology problems than can be summarised in this post. If you want to know more about those specific problems, it’s worth reading the technical appendix from the 2019 judgement against the Post Office.

What could help in a situation like this?

Thinking speculatively – the futures wheel

A large part of our service design work at Nexer centres around speculative design. This is the idea of looking forward and speculating about what the future could hold and then working backwards from a preferred future, to understand what steps could be taken now. In our work at the Department for Education, we have used futures wheels to understand what the direct and indirect consequences of a decision could be. We ask “what if we do X?” and map out what could happen as a result. This hypothetical activity gives decision makers permission to think more freely, and allows them to envision potential futures, both positive and negative.

A key benefit is that it highlights different decisions that can be made, even potentially radical ones that had not been thought of before. It can also help crystallise risks and worries, bringing people together to make plans for mitigating them. If, for example, the Post Office had done this activity when examining the 0.60% error rate, it could have mapped out how this error rate could affect Sub-Postmasters and possibly identified a better solution.

Touchpoints that failed

Touchpoints are a point of contact or interaction with a service. A user will engage with a touchpoint to achieve goals and meet their needs.

The EPOSS counter that caused all the problems

In the case of Horizon, the main touchpoint was the Electronic Point Of Sale (EPOSS) counter that the Sub-Postmaster or branch worker interacted with. This included a monitor, keyboard, mouse, a printer and card scanner as well as the computer hardware and the Horizon software on it.

The EPOSS counter could be troublesome and frustrating for Sub-Postmasters and branch staff. The problems users encountered were largely down to its poor development which I have already covered. Some problems users experienced because of those technology failures were:

- Frequently needing to reboot the computer

- The interface “locking up” and becoming unresponsive

- Transactions being recorded incorrectly

- Financial records not being correct

All of these affected the Sub-Postmaster's ability to reliably serve their customers and manage their business successfully. Over time these failures led to many Sub-Postmasters being falsely accused.

A frustrating Helpline experience

I’ve already covered how the helpline and some of its processes allowed bugs to fester. Now, we’ll examine the helpline as a touchpoint and the problems users experienced when interacting with it.

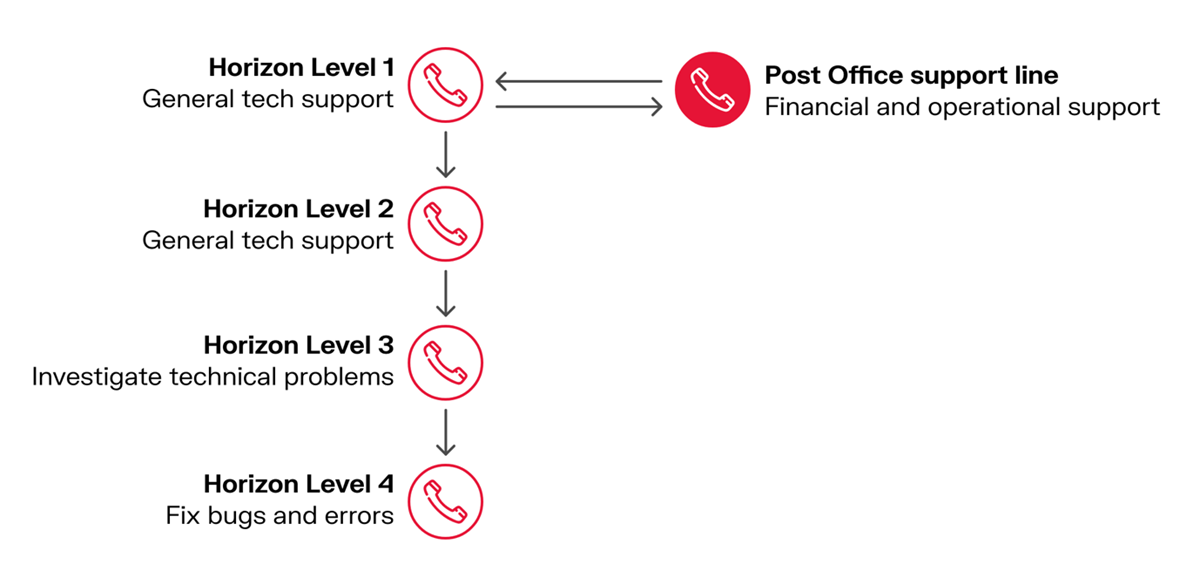

Figure 2: The structure of the Horizon helpline

When Sub-Postmasters encountered problems with their EPOSS counter, they could call Fujitsu’s helpline. This helpline featured four different support levels. Levels 1 and 2 were for general help, with Level 2 handling more complex calls. Level 3 addressed technical problems that needed deeper investigation, and Level 4 escalated issues to development teams to ensure bugs and errors were fixed.

User ping pong

Level 1 would often redirect users reporting discrepancies to the Post Office's support line. The agents on the Post Office’s support line lacked Horizon technical training and would then send users back to Fujitsu. This back-and-forth cycle could frustrate users and discourage them from seeking help at all.

“Log and flog"

Level 1 support had limited ability to help resolve problems beyond suggesting a system reboot. In fact, staff referred to the function as “log and flog”11 in that they would create a ticket and pass it on. This would be stressful for staff in Post Office branches, who may have been unable to serve customers in the meantime.

Insufficient training

Service desk staff had insufficient training on the Horizon system. Manager, Amandeep Singh from the service desk said “When you're on a phone call, you have to visualise what the postmaster is visualising” … “But we were just given routine transactions.” He admitted that he had been shown how to perform more complicated functions like reconciliation only once.

No training on how to help customers with low IT literacy

Many Sub-Postmasters calling the helpline had never used computers before... “This was the early 2000s. Many Postmasters had worked in their branches for decades and had never been around a personal computer.” As a result, some calls could take 30 minutes just to walk a user through a basic transaction. Singh remarked, “In some cases, you had to explain what a mouse was.” This created frustration among helpline teams, who were under pressure to handle more calls. Helpline staff had no training on how to assist customers with low IT literacy, leaving Post Office staff confused, frustrated, and upset by their interactions.

Downplaying concerns

It was widely reported by Sub-Postmasters that the helplines occasionally downplayed their concerns, falsely claiming they were the only branch experiencing issues.

Overall, the helpline was a poor experience for Sub-Postmasters. It negatively impacted their mental health and sense of reality, isolating them at a time when they needed support. Many Sub-Postmasters covered up shortfalls because they couldn’t get the system to work. It’s hard to underestimate the effect a better-designed and more empathetic helpline could have had in these cases.

What could help in a situation like this?

Regular usability testing

Regular usability testing is essential to ensure that products and services are functional, usable, and meet users' needs. Without consistent testing, issues accumulate and become too costly or complex to fix.

Service prototyping

At Nexer Digital, we are big advocates of service prototyping to uncover internal users’ needs and make sure they are not forgotten. In its simplest form, this can be storyboards, roleplaying or paper prototyping to name a few. Service prototyping does not have to be expensive or hyper-realistic to uncover insight. Service prototypes should be done early and often to understand pain points and address them before it becomes too expensive to change them.

Service mapping to visualise complexity

It’s important to create service blueprints that include all channels of your service, such as telephony, mail or in-person. This allows you to map out key backstage processes, seeing where there may be pain points in processes involving humans delivering a key part of the service.

At Nexer Digital, we are no strangers to this approach. On a we were asked to help redesign a service that allowed scientific researchers to put biological samples in at one end and get data out at the other. The challenge was that it was hard to track was going on and when the data might be ready. Several groups of people were involved backstage, and many different channels including emails, order forms, ticketing and finance systems. Doing this sort of activity help problems in the operational side of the service to be come to the surface and be fixed much earlier.

In Summary: Everything is connected

In reflecting on the pace layers at play in the Post Office Horizon Scandal, it's crucial to recognise their interconnectedness and the impact each one can have on the others.

When strategy keeps changing, technology must constantly react, leading to poorly executed solutions. When technology fails, it disrupts operational processes, forcing workarounds and unethical practices.

When processes are created in silos, without considering the bigger picture, the service experience becomes poor—and, as we’ve seen in this case, even damaging and dangerous.

Finally, culture eats everything else for breakfast, and it is the slowest to change. When technology disrupts an existing business model or process, we must carefully consider how it will integrate with the existing culture and what changes need to occur.

To navigate these challenges and strive for improvement, embedding service design across organisational layers is essential. As is research to understand user needs and an acknowledgement of the relationship between technology and existing policies.

Most importantly, fostering a culture centred on empathy and focused on users is fundamental. Digital transformation should aim not only to improve touchpoints for users but also to transform the organisations themselves, their operations, and the attitudes and behaviours of the people within them.

If you want to learn more about our service design work and how our team can help your organisation, please get in touch with us at: hello@nexerdigital.com.

Sources:

BSC (2021) ‘Computer always right’ law must be revisited to avoid another Post Office Scandal https://www.bcs.org/articles-opinion-and-research/computer-always-right-law-must-be-revisited-to-avoid-another-post-office-it-scandal/

Evans-Jones, Liz (2023). The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-3-7-march-2023

McDonnell, David. (2022) The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-2-16-november-2022

McDonnell, David. Holmes, Jan. (1998) The Report on the EPOSS PinICL Task Force. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/evidence/fuj00080690-report-EPOSS-pinicl-task-force

Miller, David. (2022) The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-2-28-october-2022

Roll, Richard (2023). The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-3-9-march-2023

Rose, Helen (2023) The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-4-19-september-2023

Savage, Michael. Das, Shanti. Tapper, James. (2024) ‘A tragedy is not far away’: 25-year-old Post Office memo predicted scandal https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2024/jan/14/a-tragedy-is-not-far-away-25-year-old-post-office-memo-predicted-scandal

Simpkins, John (2023) The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-4-17-january-2024

Singh, Amandeep (2023). The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-3-7-march-2023

Sweetman, Stuart (2023). The Post Office Horizon Enquiry. https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/hearings/phase-2-2-november-2022

Wallis, Nick (2021). Computerweekly.com. Fujitsu bosses knew about Post Office Horizon IT flaws says insider. https://www.computerweekly.com/news/252496560/Fujitsu-bosses-knew-about-Post-Office-Horizon-IT-flaws-says-insider